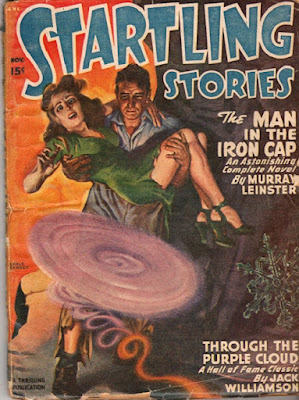

This is a pulp that I own and read recently. That’s my copy in the scan. The cover is by Earle Bergey, a little more sedate than usual and not one of his better ones, but still not bad. Unlike the fans at the time (more about that later), I’m a big fan of Bergey’s work.

I’ve been reading stories by Murray Leinster, whose real name was Will F.

Jenkins, for more than 50 years. I’m sure some of his stories were in various

science fiction anthologies I read in junior high and high school. His novella “The

Man in the Iron Cap” is the lead story in this issue of STARTLING STORIES. I’d

barely started reading it when I came across this gut-punch of a passage:

The world, of course, was bright and new and shining on its sunlit side, and

restful and peaceful and secure where night clothed it. In the countries where

the sun shone men and women worked and children played and where the stars

looked down they slept quietly.

But all assured themselves that they were secure. They were perfectly,

perfectly safe. The world was made safe by Security, which was an organization

of quite the wisest men on earth. They were at once the greatest scientists and

the most able administrators. They had the welfare of everybody in mind.

They had begun, of course, by forbidding anybody to experiment with atom bombs

because the human race could be wiped out by so few of them. They could make

all the earth's atmosphere poisonously radioactive. Then everybody would die.

But Security prevented that.

And presently it forbade the use of atomic energy as such in any form because,

of course, any generator of atomic power makes radioactivity which may escape

into the air. Not long after that, the wise men of Security learned that

someone had been experimenting with germs and by accident had created a new and

very deadly mutation.

It could have been used in biological warfare, but also it could have released

a new and very deadly plague upon the world. So Security forbade experiments

with germs. And still later a physicist discovered the principle of a very tiny

generator which developed incredibly high voltages. Beams of deadly radiation

became possible. So Security had to take steps to protect the world from that.

Security was very wise and very conscientious. It did not stop all scientific

advance, of course. Its scientists experimented very carefully, in especially

set-up Experimental Zones, with all due care that nothing could happen to

endanger the people of Earth. Which meant, naturally, that they did not make

any very dangerous experiments.

In time Security took a fatherly interest in public health because new plagues

sometimes arise in nature. It issued directives governing quarantine and

medicine in general and, of course, travel by individuals because individuals

are sometimes disease carriers. And presently it was inevitable that Security

should give advice on education, and arrange that technical knowledge should be

restricted to stable personalities.

In a complex modern civilization a single paranoiac could cause vast damage if

he were technically informed. So presently everybody took psychological tests,

and those who received technical educations were strictly licensed by Security.

Then libraries were combed and emptied of dangerous facts that lunatics could

use to the detriment of mankind.

The people of Earth were very secure. They were protected against everything

that Security could imagine as happening to them. But they weren’t free any

longer. The tragedy was that many of the guiding minds of Security were utterly

sincere, though there were self-seekers and politicians merely seeking soft

jobs and importance among Security officials.

The guiding minds believed devoutly that they served humanity by using their

greater knowledge and wisdom to protect human beings from themselves. But

somehow, knowing their own motives, they did not see that they had created the

most crushing tyranny ever known to men.

Looking around at our world, that’s chillingly prescient and would keep

this story from being published in any mainstream SF market today. It’s also a

little long-winded and repetitive, which is this story’s main flaw. Leinster

recapitulates what’s going on a lot. Also, the plot depends on several huge

coincidences.

That said, “The Man in the Iron Cap” has some real strengths, too. The

protagonist is a scientist named Jim Hunt, who has been sentenced to life in

prison for unauthorized experiments involving telepathy. He escapes, but then

he stumbles into an alien invasion of telepathic, blood-sucking creatures from

outer space that have taken over a mountainous, rural area and are gradually

expanding into nearby cities. The Little Fellas, as their mind-controlled

victims refer to them, are some of the creepiest villains I’ve ever encountered

in science fiction. This story is really a cross between SF and horror. Leinster

throws in some nice twists, as well, as Jim Hunt tries to figure out a way to

defeat the aliens, and the ending is very satisfying. Leinster expanded this

into a novel called THE BRAIN STEALERS, which was published as half of an Ace SF

Double in 1954. I haven’t read that version and likely never will, but I really

enjoyed “The Man in the Iron Cap” despite the somewhat dated writing.

I’ve been reading Jack Williamson’s work about as long as I have Murray Leinster’s. The first Williamson I remember reading is his novel GOLDEN BLOOD, which I bought in the Lancer Easy-Eye edition off the paperback spinner rack in Tompkins’ Drug Store when it was new. I really ought to reread that book one of these days. His short story “Through the Purple Cloud”, which appeared originally in the May 1931 issue of WONDER STORIES, is reprinted as a Hall of Fame Classic in this issue of STARTLING STORIES. That may be stretching it a little. The plot has an airliner flying through a purple cloud that suddenly appears in the sky in front of it and winding up crashing on a savage world in another dimension. Among the few survivors are an engineer (a lot of protagonists from this era of SF are engineers, of course), a beautiful girl, and a villainous brute. The struggle to survive and eventually get back to our own world ensues. This is mostly an action story with a little scientific speculation, but it’s well-written and moves right along at an entertaining pace. It’s actually a minor Williamson yarn, as far as I’m concerned, but I’m a big fan of his work and found it enjoyable if not quite a classic. I should note that it’s the cover story in both its pulp appearances, with the art on the WONDER STORIES cover provided by Frank Paul.

I’ve heard of British SF author John Russell Fearn for a long time, too, but unlike Leinster and Williamson, I’ve read very little by him. His story in this issue, “Chaos”, written under the pseudonym Polton Cross, is a “last days of Atlantis” yarn, in which Atlantis is a scientific paradise until something goes wrong and leads to its destruction. It’s well-written but a little dry for my taste.

The final story is “Anastomosis” by Clyde Beck, an early SF fan who published only four stories. This one is probably more fantasy than SF, a whimsical domestic comedy about a math professor, his young children, a mysterious visitor, and a gizmo. It reminded me a little of some of Robert Bloch’s humorous stories. Mildly amusing and worth a few smiles.

Wrapping things up is a lengthy editorial department/letters column called “The Ether Vibrates”. Some familiar names show up: Chad Oliver, Lloyd Arthur Eshbach, Stanley Mullen, Lin Carter, and Virgil Utter. The other correspondents are probably well-known to those more familiar with SF fandom from that era than I am. Several of them complain about Earle Bergey’s covers. One even calls them immoral. Me, I still like those Bergey space babes.

After that little digression, I should mention that the editor of STARTLING STORIES at this point in its run was none other than Sam Merwin Jr., who bought the first story under my name for MIKE SHAYNE MYSTERY MAGAZINE approximately 30 years later and had a huge impact on my career by asking me to write one of the Mike Shayne novellas under the Brett Halliday house-name. As I’ve mentioned many times before, I owe Sam a big debt, not just for the stories he bought but for the hastily scrawled but always enthusiastic and encouraging notes he sent along with dozens of story rejections in 1975 and ’76 when I was trying to break in. He put me on the path I’ve followed for almost half a century now.

Overall, I think this is a very good issue of STARTLING STORIES. If you want to check it out, the whole thing is available at the Internet Archive.

1 comment:

Love this post. Thank You.

Post a Comment